It is gratifying to note just how far project management has developed as a management discipline in its own right over recent years. I believe that much of this is driven by the clarity and focus demanded by the modern definitions of projects that have evolved. ‘A temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product service or result‘ is the expression conceived by the PMI in their Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge 5th ed.’, for instance, and the use of the words ‘temporary’ and ‘unique’ are very significant for two reasons. Firstly, they clearly differentiate the project environment from that of routine operations, such as mass manufacturing and most instances of service provision. Secondly, they lay the foundations of the tools and techniques that collectively define project management. For instance it is the uniqueness of a project endeavour that directly leads to the uncertainty therein, which in turn requires the characteristic cyclical planning and control activities intrinsic to approaches such as Demming’s Plan Do Check Cycle and the PMI’s Process Groups of Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring & Controlling and Closing.

However, helpful though this definition is, there are drawbacks. In particular to ensure applicability to all types of projects, it is necessarily, a ‘one size fits all’ approach. Whilst this is helpful in defining the project ‘brand’ and initiating key approaches, we soon reach the point when, to achieve a better ‘fit’ , so to speak, it becomes necessary to define sub-categories of projects and address their particular needs.

Programme Management is an example of this. Programmes are unique and temporary and so conform to the above definition: they are projects. However, they are a special type of project with particular characteristics and it has been deemed helpful to sub-categorise these projects under the name of Programmes so as to enable the development of particular and bespoke tools and techniques (and standards and qualifications) that apply only to them.

I believe there is a compelling need to identify and treat another sub-category of projects in this way: those projects delivered by Supplier Organizations (SO).

Conventionally, either directly or by implication, the project management bodies of knowledge focus on the role of an Owner Organization (OO). These are the bodies that commission the project and it is they who will own the completed asset or capability (the project’s product or deliverable) and reap the reward of those benefits realised from its operation. Examples would include a car manufacturer commissioning the construction of a new factory and profiting from its subsequent use.

By contrast, Supplier Organizations (SO) are those parties that are engaged by the Owner Organization (OO) to provide the goods and services that are required to create the project asset or capability. Within the example of the car plant above, a Supplier Organization (SO) would be the architects practice engaged by the Owner Organization (OO) to design the building for the new facility. Their reward will not stem from ongoing ownership of the product; it will be the consideration, i.e. the payment to which it is entitled by dint of the procurement contract established with the OO.

The first reason why I believe this category of projects needs special attention is its widespread relevance. If we consider the above car plant project, we would expect a very significant number of Supplier Organizations (SO) providing the myriad bespoke equipment and services required by the project. We would also expect each to appoint a project manager (PM) to both liaise with the client and internally manage their own scope of supply. So, for each significant project there may be many PMs employed by SO, but there will be only one PM employed by an OO. It is my contention that this ratio is repeated across most projects and so most of the individuals engaged in the management of projects do so for Supplier Organizations (SO) rather than Owner Organizations (OO).

The second reason for special attention is that projects managed by SO are significantly different from those of an OO. Consider the following.

Reason for engagement. As discussed above, OO engage in projects to secure the benefits of asset ownership and operation whereas SO engage in projects to secure a consideration. This is a fundamental difference which has significant and far-reaching implications, some of which are expanded upon below.

Principal controlling document. For an OO the most important document to which all contentious decisions ultimately defer to is the endorsed business case. For the SO it is the contract agreed with the client.

Risk exposure. The nature of risks faced by SO and OO are different. For instance, only OO bear ‘business case risks’: risks which do not threaten the creation of the project product but do threaten the realisation of operational benefit. Within the car plant, an example would be an unforeseen hike in oil prices supressing the market demand for new cars. By contrast, OO are not faced with the commercial risks faced by a SO when dealing with a very small number of very high value projects (contracts), such as payment default by the OO.

Marketing and selling as project management activities. For the OO, the prelude to a project involves identification of operational benefits; defining the requirements of a product (or products) that will facilitate the realization of these benefits; selecting the preferred product (option); and establishing and endorsing a business case contrasting these operational benefits to the costs and risks of creating the product. For the SO the prelude is the activities of marketing and selling.

For these, and other reasons I believe that the two scenarios are sufficiently different to warrant their own models and skill sets. The following is a brief summary of those described under the headings of Soft Skills, Structure and Hard Skills.

Soft Skills. Projects are delivered by people for people and although it easy to focus on the very obvious tools and techniques of project management, what really matters is the less obvious and abstract interpersonal skills. Managers need to understand their subordinates, their imperatives and their instincts, and in this respect Supplier Organizations (SO) have a particular dilemma. Consider the following.

Soft Skills. Projects are delivered by people for people and although it easy to focus on the very obvious tools and techniques of project management, what really matters is the less obvious and abstract interpersonal skills. Managers need to understand their subordinates, their imperatives and their instincts, and in this respect Supplier Organizations (SO) have a particular dilemma. Consider the following.

- Project teams are temporary groups of individuals brought together to create something that is unique, and their ethos can be summarised as ‘deliver and disband’.

- Manufacturing organizations, by contrast, are permanent institutions that produce (preferably) identical products and whose ethos is all about survival.

Unsurprisingly, these two paradigms lead to very different structures, and the adoption of very different managerial tools and techniques. A SO that is servicing a project with bespoke goods or services has a foot in either camp and, whilst the technical challenge of integrating these two approaches to management is formidable, to my mind there is something more significant at play; a clash of cultures.

‘Culture’ is the expression used to describe the special ensemble of thought patterns, instincts, attitudes, values, accepted norms, customs and language that is shared by a group, and their emergence and refinement over time is not a random accident. They develop as an idealised response to the particular environments and challenges faced by each different group, and the two paradigms described above represent two very different challenges. For this reason, with ‘a foot in either camp’, it can be said that SO stand astride a fault line between two very different cultures.

Attitude to changes, importance of individual customer focus, appropriateness of rule based governance, importance of stability of structures, importance of stability of numbers, appropriateness of different incentives, importance of job security, terms of engagement, favoured attributes of employees, favoured attributes of employers, prioritisation of efficiency over effectiveness, and many more, are each areas that I have identified, where the culture favoured by each of the paradigms adopt polar opposite views.

Achieving an accommodation between these two cultures is not straightforward but I believe it is of paramount importance in determining the success or otherwise of SO. I further believe that practitioners are poorly served by the literature on project management, which offers scant advice for identifying and dealing with these cultural conflicts.

Structure. Projects, like ourselves, are all different: each is unique. However, again like ourselves, projects do have some common features. Most notable amongst these is a life cycle model. The transition through the phases of infancy, childhood, adulthood, parenthood etc. is common to us all. This forms the basis for understanding of the human condition, and the transitions from one phase to the next are associated with the making of important decisions (‘shall I finish my education and start work?’, ‘am I ready to be a parent?’).

The division of projects into phases and the identification of key decision making points in between is well accepted by the practitioners of project management. The PMBOK® Guide 5th ed. suggests that projects can be represented by a lifecycle consisting of the phases of

- Starting the project

- Organizing and preparing

- Carrying out the project work

- Closing the project

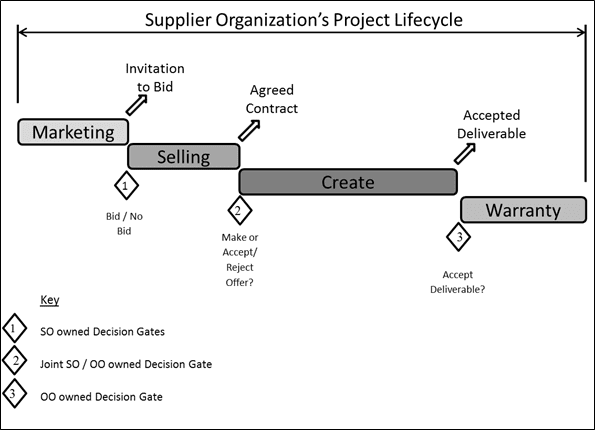

This project lifecycle model represents a very broad brush approach. To ensure its relevance to all projects it has to be that way, but when addressing just a sub-category of projects it is possible to more specific. The projects of Supplier Organizations (SO) are such a sub-category and warrant their own dedicated lifecycle model. I propose that shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Supplier Organization’s Lifecycle

As can be see, the identity of the phases and the decision gates represent a radical departure from the conventional model associated with the lifecycle of an OO project, and it highlights the predicament of the SO.

The early phases of projects are when most influence can be exerted over the project and are disproportionally important to the project’s ultimate success. As discussed above, for the SO project, these phases are the activities of marketing and selling. Marketing is concerned with ensuring that the right product is put in front of the right customer at the right time, whereas selling is the process of persuading prospective customers to buy your product for the maximum price and on the most favourable terms.

The SO simply must have expertise in these vital areas, not least because it is far more important to an organization to choose the right project than it is for them to manage it well. Also, the profit to be secured by the SO is as much determined by the selling price as it is by the cost. Given this importance it is therefore unfortunate that so few books on project management address these topics within the context of projects.

The identity and nature of the decision gates also points to another key aspect of the business of the SO, namely that their behaviour is dominated by the contract they agree with their client, the OO. One consequence of this is the decreasing autonomy enjoyed by the SO. The first gate (Bid/No Bid), when the SO decides whether to submit to the sales process, is wholly owned by the SO, however the second gate (Make or Accept / Reject Offer) relates to whether a contract should come into being and since this requires the agreement of both parties, it is shared by both the SO and OO. By contrast, the final decision (Accept Deliverable), for all intents and purposes, is wholly owned by the OO. Unlike an OO, post-contract, the SO is not able to mitigate its risk exposure by prematurely terminating their project.

A second consequence of the SO predicament is the existence of the Warranty Phase. The SO lifecycle terminates at the point when their contractual obligations expire. This exact point is usually determined by aspects of law and is seldom clear cut. At minimum it means that the obligations extend beyond the completion of the work. This ongoing risk exposure needs to be acknowledged not least by this dedicated phase within the SO lifecycle.

Hard Skills. The commercial astuteness required of a SO PM, especially in respect of their aptitude for contract administration, is an order of magnitude above that which, generally, is required of an OO PM. Whereas an OO project may not involve the establishment of any contracts, by definition, each SO project will involve at least one. The SO PM must be intimate with them, and the consequential rights and obligations of each party. Consider, for example, the management of changes. To an OO, changes are almost always costly and unwelcome intruders into their projects, but for SO they often represent their best opportunity for maximising profits. Canny SO PMs can dramatically extend their contract value (and profit) by the diligent pursuit and negotiation of favourable change, a process which encompasses those disciplines of marketing and selling. This is one reason why these key SO competences SO cannot be left solely in the hands of their sales persons and marketers.

Hard Skills. The commercial astuteness required of a SO PM, especially in respect of their aptitude for contract administration, is an order of magnitude above that which, generally, is required of an OO PM. Whereas an OO project may not involve the establishment of any contracts, by definition, each SO project will involve at least one. The SO PM must be intimate with them, and the consequential rights and obligations of each party. Consider, for example, the management of changes. To an OO, changes are almost always costly and unwelcome intruders into their projects, but for SO they often represent their best opportunity for maximising profits. Canny SO PMs can dramatically extend their contract value (and profit) by the diligent pursuit and negotiation of favourable change, a process which encompasses those disciplines of marketing and selling. This is one reason why these key SO competences SO cannot be left solely in the hands of their sales persons and marketers.

Intrinsically entwined with commercial astuteness, is risk management. Risk management is not the sole preserve of SO, it is vital to OO as well, but the type of risks and their mitigation is different. As mentioned above, SO are not exposed to ‘business case risks’ but it is most likely they are very heavily exposed to ‘product based risks’. This is because the OO has most likely taken the Transfer option for such risks and engaged the SO, perhaps solely, because they can both minimise their likelihood and bear their consequences. Rather than shying away from such ‘product based’ risks, astute SO will welcome them since they will appreciate that the greater the risk, most likely, the greater reward. There are though, many hazards lurking here and to mitigate them the SO will rely on a very sophisticated understanding of different procurement chain configurations, different contract types (sub-contracts, consortia, joint ventures, framework contracts etc.) and different reimbursement types (lump sum, target cost, cost reimbursable etc.). They will also rely on their special instincts, for instance, ensuring the clarity of scope pre contract takes on board a special relevance for SO.

Another consequence of the special risk exposure of the SO rather than the OO is the timing of activity within the lifecycle. For instance, when contemplating acceptance of a contract involving a firm price and a firm completion date, the SO may engage in very detailed planning much earlier than an OO may choose to do so. This is because the activity is undertaken not as a preparation for execution but as means of commercial risk mitigation, since it is the only way of securing a sufficiently precise estimate of cost and duration.

The reliance of a SO on one (or very few) customers also poses special risks. Letters of Credit, and Bank Bonds are not things that OO very often have to deal with and yet to many SO they are a core aspect of their business.

To conclude. If we were to draw a Venn diagram and represent the contents of the PMBOK® Guide as one circle, and another to represent the skills tools and techniques that I believe are required of a SO PM, there would be a very considerable overlap. The former would cover most of the latter and the latter would occupy almost all of the former. This and the other bodies of knowledge, therefore, are hugely relevant to SO, but, crucially, within our diagram, there will be margins. There are aspects of the PMBOK® Guide that are of little relevance to the SO, but there are many more techniques, tools and knowledge that are of enormous relevance to just SO projects that are not addressed in this or other project management bodies of knowledge. Further, since I believe that more project practitioners manage projects on behalf of SOs than do on behalf of OOs, I feel a huge constituency is being let down. To address this I feel the time has come to accept that one size does not fit all and Project Management for Supplier Organizations should be recognised as a significant sub-category, and, like Programme Management deserves special treatment.