The greatest challenge facing project management in the 21st Century is managing the shift from the ‘command and control’ paradigm based in the theories of ‘scientific management’ developed in the early 20th Century to a recognition of the inherent uncertainty and complexity involved in managing every project, and in particular, projects focused on the outputs of knowledge workers such as ICT and ‘Business Change’ projects.

Project ‘control systems’ (schedules, cost plans, etc) don’t control anything and to a large extent, neither can project managers. People control their actions and the environment dictates many ‘uncontrollable’ variables. Apart from providing ‘guidance’, which if accepted will potentially influence the decisions and actions of the project team, project plans can only provide a tool for estimating the likely levels of uncertainty in each element of the plan and then measuring the actual degree of variance as it occurs. Understanding the variance provides valuable management information but how effectively this knowledge can be used depends on the circumstances of the project.

The traditional project management paradigm (philosophies and assumptions) has some validity when the goal of the project remains stable and the work required is largely straightforward and obvious (eg the construction of a well designed, traditional, building). The ‘knowability’ and ‘understandability’ of both the project work and its intended deliverable is implicit in the relative success of project management in traditional industries such as construction and engineering. The value of the paradigm becomes less certain when the ultimate project goals are ‘to be discovered’ or change during the course of the work[1] (eg delivering a cultural change program) or when the nature of the work changes from essentially manual tasks that can be observed and measures to knowledge work occurring in a person’s mind.

Project management writings of the last few years suggest that ‘people skills’ and leadership are important attributes of a successful Project Manager and effective stakeholder management is definitely seen as a major item in delivering project success[2]. Within this emerging people centric paradigm, complexity theory helps us to understand the social behaviours of teams and the networks of people involved in and around a project. The idea of complexity applies equally to small in-house projects and large complicated programs; in this regard, ‘complexity’ is not a synonym for ‘complicated’ or ‘large’.

Applying Complexity Theory[3] the nature of a ‘project’ can be described from the perspective of the ‘knowledge workers’ or ‘actors’ engaged in the creation, execution, delivery and closure of the project. Consequently, the purpose and use of project management artefacts such as Schedules and EV Charts changes from ‘control’ documents to communication tools to influence each of these ‘actors’ (stakeholders) behaviours.

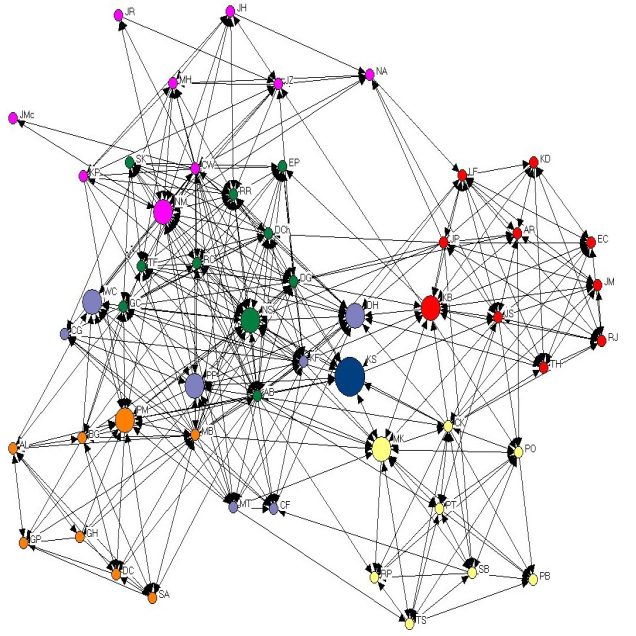

Two relatively recent views of projects are the ideas of projects as TKOs and the project team as a social network within a larger social network comprised of the projects stakeholders and surrounding community. These ideas have much in common.

- Viewing a project as a temporary knowledge organisation (TKO) moves the focus of project management from the observation of the output of the project (its deliverable) to the processes needed to transform inputs received by the project team into the project deliverable(s). This transformation is achieved by the gathering, melding, processing, creating and using of knowledge. The concept of a TKO represents a shift from viewing projects as ‘tools’ applied to solving problems, where people are outside the project; to the creation of a sense-making community of practice by the people involved in the project. This requirement for project team members to act as knowledge workers leads to additional expectations of the leadership qualities of the project manager[4].

- Social Network Theory is similar. A social network is a social structure made of nodes (which are generally individuals or organizations) that are joined by some form of relationship. The shape of a social network helps determine the network’s usefulness to its individual members. The project team is a social network and it exists within a larger network primarily consisting of the project’s stakeholders. The project network can be considered as being both independent of the larger organisational network and an integral part of it.Each network contains a level of ‘social capital’ – the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and/or derived from the network of relationships that connect its members. The two key aspects of social capital are the ‘know how’ required to create and deliver the project outcome and the ‘willingness’ to exert effort to achieve the project outcome. Importantly, the level and availability of social capital within a social network is not fixed, it can be increased by developing:

- a more effective network by creating stronger relationships (links),

- a better alignment of the actor’s objectives through developing clear, agreed goals,

- effective collaboration and leadership (ie by developing a ‘high performance team’).

Conversely social capital can be dissipated by ineffective leadership, lack of agreement, contradictory visions, etc (ie by allowing a dysfunctional team to develop).

Combining these ideas, it is reasonable to assert that it is the actual transfer of relevant existing knowledge through the ‘social network’ that allows the project team, functioning as a TKO, to develop the new knowledge needed to create the project’s deliverables. It is also important to note the actual transfer and creation of knowledge and the implementation of the ‘new knowledge’ to create the project deliverable is absolutely controlled by the willingness of the actors within the network to engage positively in the work. Therefore, effectiveness of this process is constrained:

- in part by the extent of knowledge actually available to the network,

- in part by the efficiency of the network in transmitting the information to and between the actors who need to make use of it, and

- in part by the willingness of the actors to actively engage in the processing and implementation of the knowledge in an aligned and effective manner.

The observation of a ‘high performance team’ is evidence of the knowledge processing and social networking systems working effectively.

The consequence of accepting these ideas is to shift the focus of ‘project management’ from the object of the project to the people involved in the project (ie, its team members and stakeholders), and to recognise that it is people who create the project team, work on the project deliverables and close the project. Consequently the purpose of most if not all project ‘control documents’ such as schedules and cost plans shift from being an attempt to ‘control the future’ – this is impossible; to a process for communicating with and influencing stakeholders to encourage and guide their involvement in the project and create a jointly held objective for the team to work towards achieving.

The outcome of the project seen from these perspectives is under perpetual construction by the project team itself. The thousands of individual decisions made by each of the people in the team, every day the project is working, ‘create’ the future:

- different information, will lead to

- different decisions, which will cause

- different outcomes, leading to

- a different ‘future’!

And one of the key influences on the multitude of decisions being taken by team members every day should be the project plans and schedules, updated, adjusted and agreed by the project team.

The consequences of each individual decision is uncertain and the response of individuals and the team as a whole to each new decision and stimulus is influenced by concepts such as non-linearity and ‘tipping points’ but with skilled management, the desired outcomes can emerge from the ‘chaos’ of the teams interactions.

However, this is not a certain process! Complexity theory, as linked to TKOs and Social Network theory, suggests that the creation of a successful project outcome will always be an uncertain journey and the path to success or failure can and will be influenced by the actions and attitudes of the actors within the project team and the effect of actions by other stakeholders around the team. The key element is how effectively the project team uses its social network to gather the resources (knowledge and support) needed to create success, and the challenge of project management is helping and encouraging this process.

The key conclusion to be drawn from this post is that successful project management is a far more complex process than simply dealing with the iron triangle of time, cost and output first described by Dr. Martin Barnes in 1969. Successful project managers in the 21st Century will develop and lead high performance teams that create project success through the effective use of the ‘social capital’ within their networks, to proactively manage the expectations of their stakeholders and then deliver the projects outputs in alignment with those ‘managed expectations’.

[1] For more on project typology see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1072_Project_

[2] See: Avoiding the ‘Successful Failure’: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/Resources_Papers_046.html

or visit: http://www.stakeholder-management.com

[3] For a brief overview of complexity see:

http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1058_Complexity_Theory.pdf

[4] See: Project Relationship Management and the Stakeholder Circle pp18: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/Resources_Papers_021.html

So informative! This is one of the best analyses I’ve seen of the current state of Project Management and team leadership in general.

The hard and fast laws of the past are more of a loose framework to which we apply service, leadership, and social capital.